The gist of PBE is that education should be structured around knowing and understanding the Big Ideas, being able to do and perform those Important Skills, becoming students who learn and retain because they understand what the school was teaching.

There are several things that have pushed this initiative; most of the concerns are with the fact that so many kids seem to drift through high school (and especially HS math) without actually retaining anything. Of course, many students passed because they deserved to, because they understood the material and were ready for the next level. On the other hand, students have also "passed" by:

- being good at only a few topics but their average was above a 60.

- sitting like a lump and getting passed on. "It's all about Seat Time."

- bringing a pencil everyday, always handing in homework (even if they didn't actually learn anything from it) and having good attendance. "She's a GOOD kid."

- expending "Great Effort". "He really tries HARD."

- Courses are comprised of a few Big Ideas and a lot of filler that has gathered in the margins over the years. Reformers argue that we should focus on those Big Ideas instead of on the filler.

- What's so special about 120 hours of class-time? What if a kid needs 135 or only 80 to master the material? Reformers ask why every class goes for 180 days, 45 minutes a day.

- Teachers giving some kids a passing grade allowing them to move on to Algebra Two, just to get rid of him or to allow him to graduate.

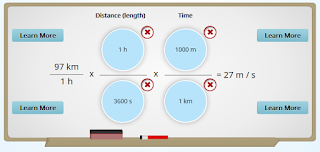

- You don't measure understanding of a concept by simple repetition of a question.

- Percentages are more precise than accurate.

- Fine-grained reporting leads to a "Horse-Race" mentality in students and parents. "I'm better than you by a point."

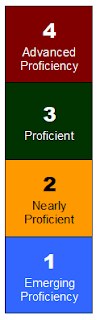

- Marking a question as 4 points out of 5 is less informative than a comment or some type of written feedback.

- Learning is a process that shouldn't be measured only once. Practice shouldn't be included in the grade, especially if the student had help.

Let's be honest here. There are a lot of adults who walk into meetings who begin by saying "I was never very good at math." There are memes aplenty that laugh at us math teachers saying "I've never had to factor a trinomial in my career. Everything I've ever done was done with 7th grade math."

Students have their own version of this game, "When am I ever gonna have to use this?" and then they promptly shut down if the answer doesn't fit into their narrow view of their future life and career.

Reformers claim, "Clearly something isn't working."

Despite the fact that the most important problems that exist in traditional education won't be solved by switching to PBE, the switch is worthwhile in my view.

The most important problem is that someone has to subjectively measure the student's performance.This has been the problem for centuries and it won't change. There are so many ways that this judgement can be altered, massaged, changed, or mangled.

Every teacher knows it.

- "Why did you give that grade to my kid?"

- "You can't fail a kid if you didn't contact the parents."

- "She didn't deserve that grade. She worked so hard."

- "Do you really want him back in your class for another year? He's taken this same course two times already."

- "If I fail this class my parents are going to kill me."

- "Did you tell his parents every week that he wasn't doing his work? I don't see any record of this in the contact log."

- "What are you going to do to help him pass?"

- "Why didn't you assign him to afterschool help?"

- "My son was always the best in his class in math, until he had you."

- "I looked at her test. She should have gotten full credit on this question, and that one isn't wrong. You have to give him a 90."

- Sometimes it's less subtle: "I'm gonna break your fucking arms if you fail my son. He only needs this one fucking math credit to graduate. I know where you live. I'm going home to get my gun."

Under PBE, however, we have an opportunity to reframe education. We're going to measure only what they know, and focus on the Big Ideas.

- Random quizzes on the way to understanding don't count. Only understanding counts.

- Homework that was done with other people's help doesn't count. Only understanding counts.

- The "Gentleman's C" is no longer a thing.

- "Pity points" is no longer a thing.

- "Extra Credit" is meaningless.

- A 90% on Order of Operations can't mask a 50% on linear functions.

- No more marks of 89.5% being considered "better" than 89%.

- No averages of 60.001% just to allow a student to pass.

Maybe.

or maybe not.